Trying Out the Ptyxis Terminal Emulator

In my years of using GNOME, I have been using GNOME Terminal, and it has served me well. There has been a newer GNOME Console; while it has a few nice new features, it lacks a small feature that GNOME Terminal has and I depend on, so I have stayed with GNOME Terminal. Now, a third terminal emulator option for GNOME, Ptyxis (TIK-sis), has appeared. I tried it out recently and quickly found myself liking it, though my declaration that it would be a good-enough replacement of GNOME Terminal for myself came only after I spent a few days tinkering with it.

Backstory

I have been satisfied with GNOME Terminal. It still uses legacy GTK 3 as of now, but I generally value a program’s functionality and capability more than its technical stack. Still, it has a small issue that bugs me every once in a while. Occasionally, after I close a tab or restore a maximized terminal window, the window shrinks and displays one fewer row each time I switch from it to another window. It looks like GNOME Terminal’s issue tracker already has a ticket for this issue; that ticket was opened in 2019 and is still open at the time of writing, after 6 years.

I can definitely live with this small issue because it is so occasional; in fact, I have been doing so. However, this issue has also prompted me to search for other great terminal emulator applications a few times. As mentioned, I looked at GNOME Console, and a feature it did not have – and still does not have yet – is maintaining terminal dimensions (especially the number of rows) when a new tab is opened. Instead, GNOME Console maintains the window size (i.e., the number of pixels in the window itself). Opening a new tab causes the tab selector to be shown, which occupies space on the user interface. Therefore, to maintain the same window size, the window area for displaying text in the terminal itself must be shrunk. For example, after opening a new tab in a single-tab window with terminal dimensions 80 columns × 24 rows, GNOME Console reduces terminal dimensions to 80×21. On the other hand, GNOME Terminal maintains terminal dimensions and increases the window size for the tab selector in this case, so all terminals still remain at 80×24 after a new tab is opened. As a personal preference, I would like terminal dimensions to stay constant and rather have the window size increase.

Therefore, after I installed Ptyxis, the first thing I checked was whether it would maintain terminal dimensions after I opened a new tab. I was delighted to see that it would. A quick exploration into the application showed me that Ptyxis has counterparts of all the GNOME Terminal features I had been relying on, so this time, I did not immediately uninstall it like I did GNOME Console.

Integration with Other GNOME Components

To many users, tinkering with a terminal emulator application involves customizing its appearance; this statement is true on me too to some extent. However, the most interesting part of my journey in switching to Ptyxis was not about how it would look; instead, it was about ensuring that GNOME would use Ptyxis as the default terminal emulator, so if I eventually wished to uninstall GNOME Terminal, I could do so without breaking other GNOME components’ functionality. I spent some time on this and was fortunate to find a solution, so I am introducing the solution early in this article for those who want to achieve the same effect to reference.

I found two integrations of GNOME Terminal with other GNOME components: the

“Open in Terminal” context menu option in GNOME Files (a.k.a. Nautilus), and

being used to launch a terminal-only desktop entry (i.e., a .desktop file

with Terminal=true set). With vanilla GNOME, when Ptyxis is installed but

GNOME Terminal is not, that context menu option will disappear, and in the

Activities overview, clicking an icon of a terminal-only desktop entry does

nothing.

To let these GNOME components use Ptyxis instead of GNOME Terminal, two software packages need to be recompiled with changes to their source code (i.e., patched): GNOME Files and GLib.

GNOME Files

GNOME Files needs to be recompiled with this patch applied, which is from Fedora. Fedora Workstation has switched its default terminal emulator to Ptyxis in Fedora 41, and it no longer installs GNOME Terminal by default, so Fedora has been patching GNOME Files to let it integrate with Ptyxis.

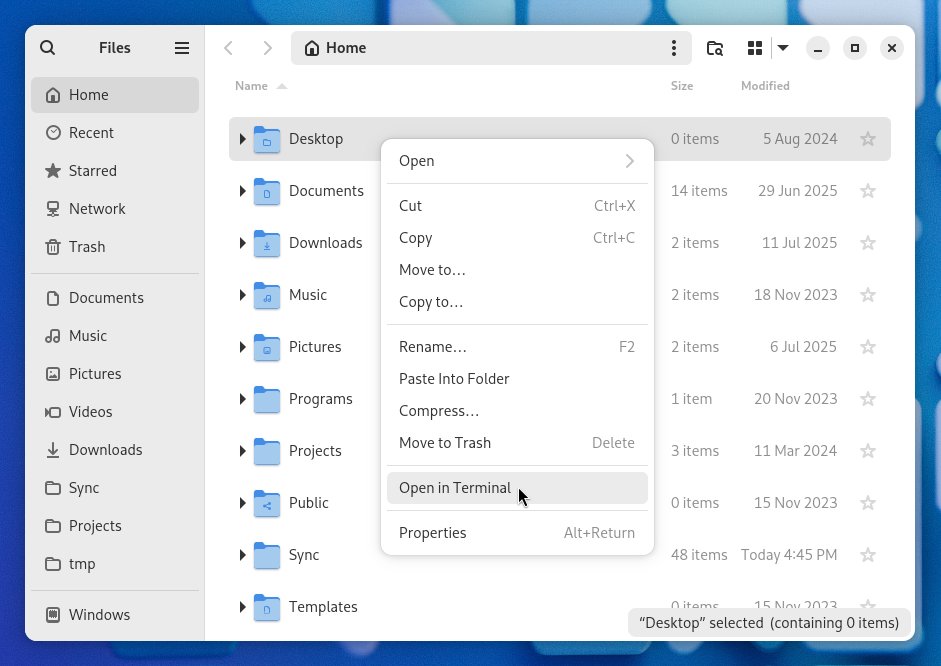

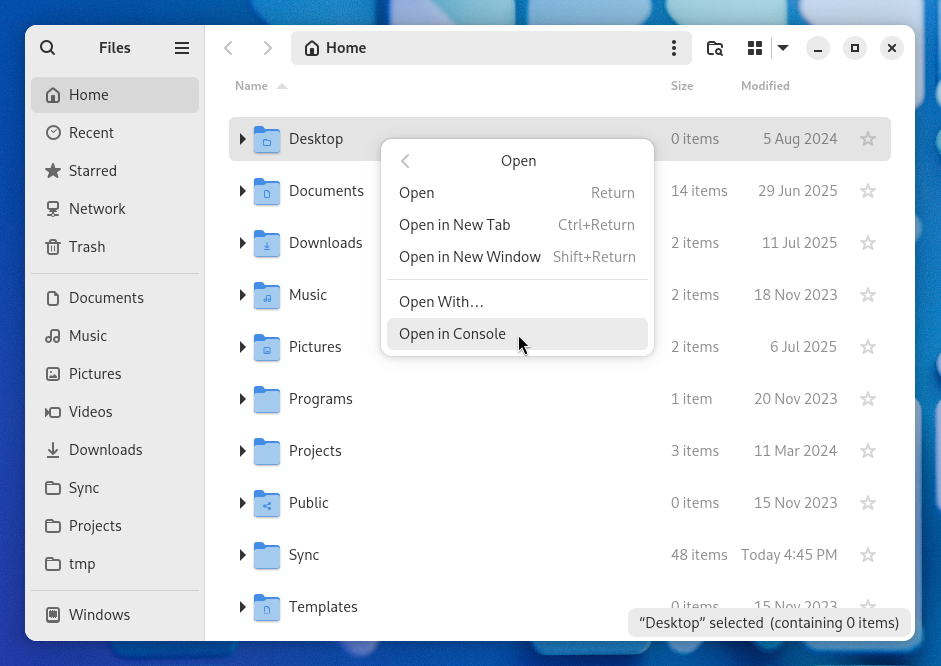

With this patch applied, when Ptyxis is installed, GNOME Files will show an “Open in Console” option in the context menu, which opens Ptyxis. In the current directory’s context menu, this option is directly available in the first-level menu. However, in a subdirectory’s context menu, this option is in the “Open” secondary menu, unlike the “Open in Terminal” option for GNOME Terminal in the first level, so unfortunately, in this case, two clicks are needed to do something that previously took just one click (quite like many user experience changes in Windows 11)…

It is worth noting that this Fedora patch replaces references to GNOME Console

(rather than GNOME Terminal) in GNOME Files’ source code with references to

Ptyxis. First and foremost, the “Open in Terminal” option (for GNOME Terminal)

and the “Open in Console” option (for GNOME Console, or, after the patch is

applied, Ptyxis) are implemented differently: the former is added by a GNOME

Files extension that comes with GNOME Terminal

(/usr/lib64/nautilus/extensions-4/libterminal-nautilus.so), whereas the

latter is added by GNOME Files itself when it detects that GNOME Console is

installed. This Fedora patch only affects the latter option. In fact, after

applying this patch, if both GNOME Terminal and Ptyxis are installed, both

options will be available in the context menu. Also, this means that it is no

longer possible to launch GNOME Console from GNOME Files after applying this

patch. Personally, this is not a problem to me because I don’t use GNOME

Console.

GLib

GLib needs to be recompiled with this patch applied, which is also from Fedora. This patch adds Ptyxis to the list of known terminal emulator applications in GLib’s source code. Through this patch, I learned that GNOME Shell launches a desktop entry through GLib utilities instead of solely by itself.

This could be a good patch to merge into the upstream GLib code, so on all

Linux distributions, GNOME Shell could launch a terminal-only desktop entry

with Ptyxis, and distributions would not need to carry downstream patches like

Fedora is doing. That said, GLib upstream has already rejected a similar

patch in favor of xdg-terminal-exec. xdg-terminal-exec

is a proposed XDG specification that will provide applications with an

interface to register themselves as terminal emulators; however, the

specification was initiated 6 years ago and is still not part of official XDG

standard yet! The good news is, it is still being updated recently.

Hopefully, xdg-terminal-exec or something similar (like xdg-default-apps)

can be ratified soon, so this patch will no longer be necessary.

Applying the Patches on Gentoo

I am using Gentoo, which is designed to allow users to compile the system’s

software packages from source code, so I can easily apply these patches to

GNOME Files and GLib by adding them to Portage, Gentoo’s default package

manager, as user patches. For those also using Gentoo, the packages to be

patched are gnome-base/nautilus and dev-libs/glib.

Color Palettes

Having taken care of Ptyxis’ integration with the rest of GNOME, I moved on to what everyone likes to show off: the terminal’s appearance.

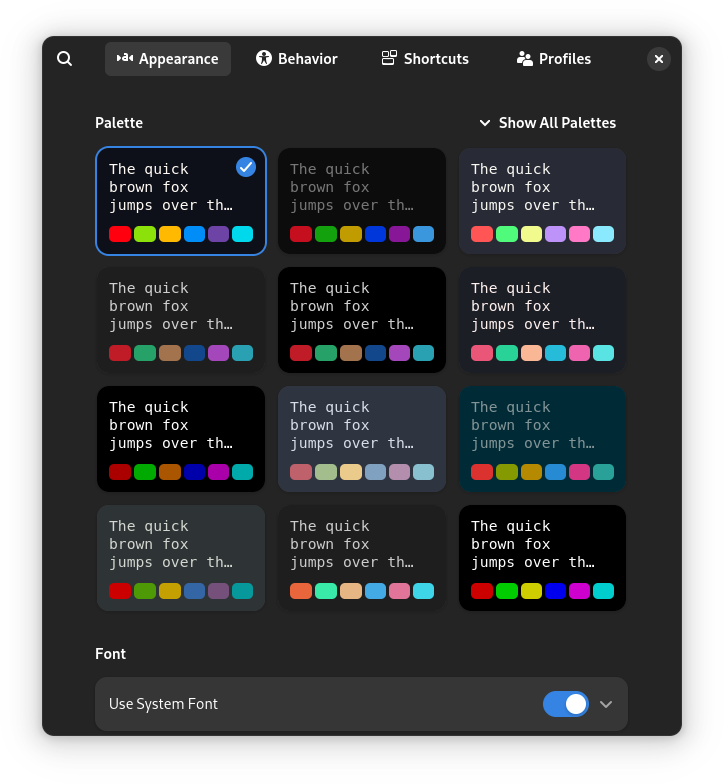

Ptyxis does offer a lot of preset color palettes and a GUI selector of these preset palettes, but as of version 47.13, its GUI does not provide users with the ability to define their own color palettes or customize the individual colors of a palette. On the other hand, GNOME Terminal allows for full color palette customization from the GUI. Therefore, I initially thought that Ptyxis lacked a full color palette customization feature.

However, through an online search, I learned that Ptyxis still supports full

color palette customization; it just needs to be done through configuration

files, not the GUI. Users can define their own color palette by creating a

.palette file and placing it under the correct path, which is documented in

the Ptyxis project’s README file. To create a

custom .palette file, users can consult the built-in preset

palettes’ .palette files as examples.

I like the fact that Ptyxis loads custom color palettes from plain-text

configuration files: this makes it easy to back up and restore these palettes.

In comparison, GNOME Terminal stores custom color palette settings in dconf,

which is like GNOME’s counterpart of Windows Registry. It is possible to

export and import dconf settings through plain-text files like Windows

Registry’s .REG files, but an extra export and import process is required for

backup and restore, which is less convenient.

Perhaps the lack of GUI for customizing color palettes is not a huge issue for

Ptyxis given that it regards developers as its primary user group: its README

says it is “engineered… for modern development workflows within the GNOME

desktop, where local containers are first-class citizens.” Of course,

developers are well versed in using configuration files, and many of them also

prefer plain-text configuration files to binary settings database like dconf

and Windows Registry. I think it would still be great if Ptyxis’ GUI could

just include a piece of text telling users that they should use .palette

files instead of the GUI to customize color palettes, so the feature is easily

discoverable at least.

Preset Color Palettes

Because I had several computers on which I might install Ptyxis, I still

decided to first try and find a preset color palette that I liked. After all,

if I would create my own color palette, and I would like to have the same

terminal appearance on all the computers, then I would need to deal with the

hassle of copying my .palette file to each computer. If I used a preset

color palette, I could just choose it on all my computers without having to

copy a .palette file first.

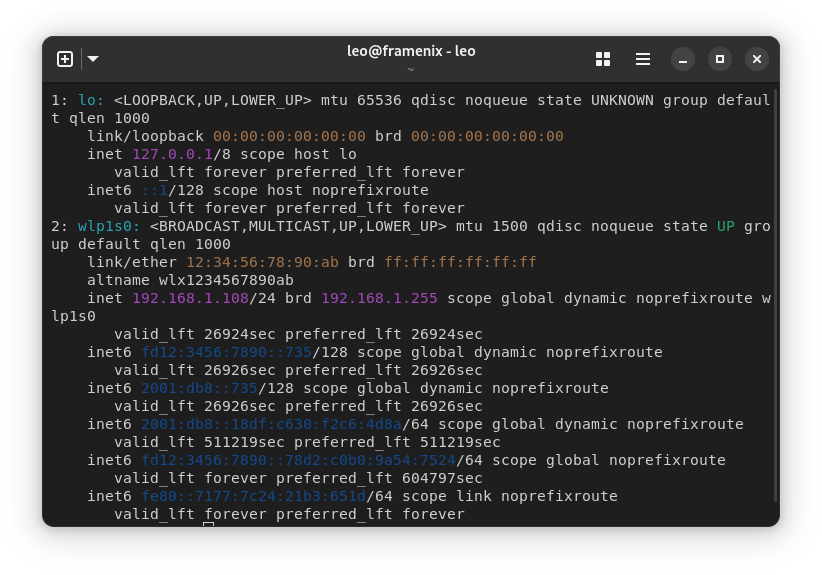

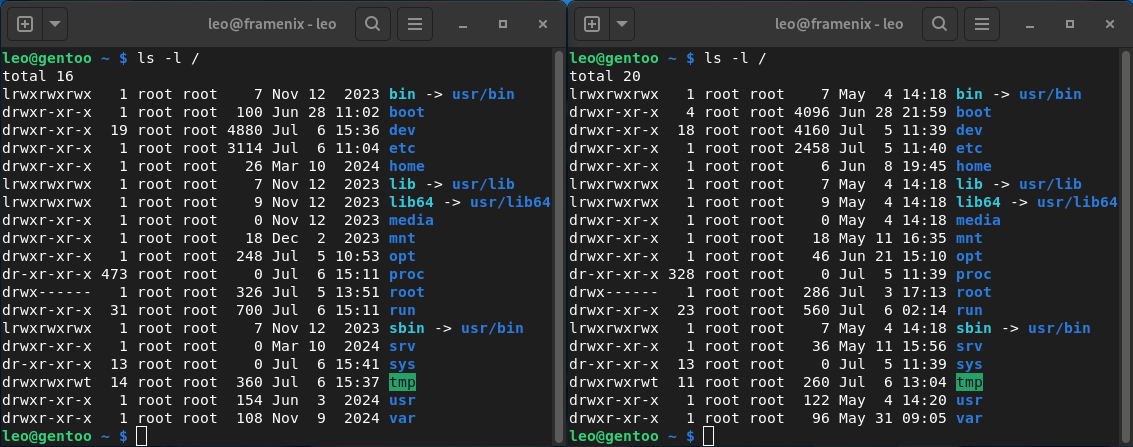

The default “GNOME” palette almost became my favorite. At least to me, its

dark blue color’s contrast to a dark background looked poor, making text in

this color not very readable; this is shown by the IPv6 addresses (inet6) in

the screenshot below. On GNOME Terminal, I actually had been using its almost

identical “GNOME” palette as well, but I would edit the palette there and make

the dark blue color brighter for this reason. I could surely do so on Ptyxis

again by creating my own .palette file, but I would not need to create the

file if I could find another good-looking preset palette.

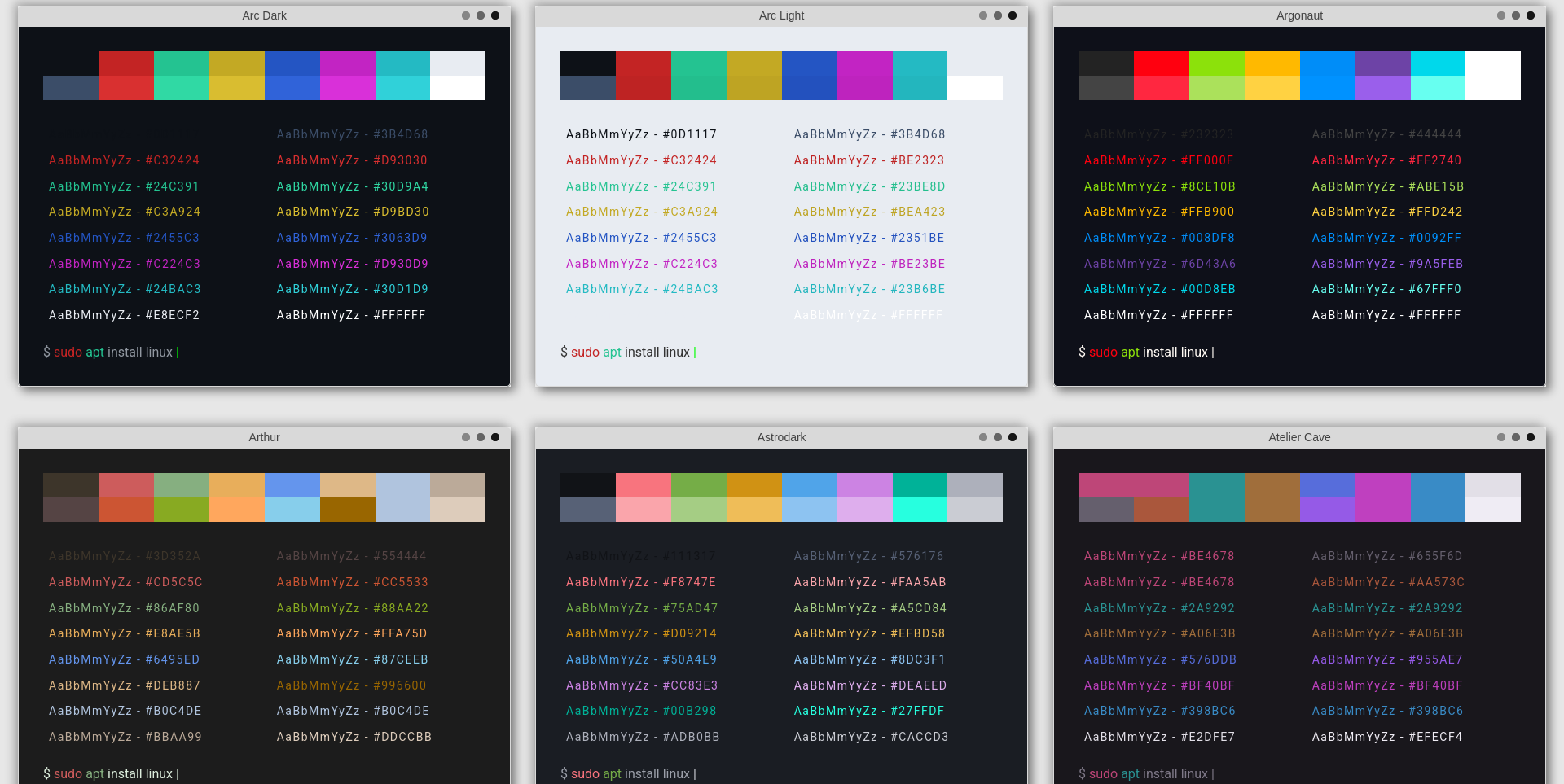

Ptyxis has more than 200 preset color palettes, and I tried to look through all of them. Eventually, I chose Argonaut. Its default text color is sufficiently bright, the background is sufficiently dark, and the contrast among the different colors is good – even when night light is on. I only wish that Argonaut’s dark purple color could be brighter. My next favorite was Ibm3270, but when night light was on, I could barely tell blue text from white text with this color palette.

For those who want to compare and choose a preset color palette, I recommend this webpage from Gogh as a resource. Most of Ptyxis’ preset color palettes are from Gogh, so this webpage serves as a comprehensive preview of many of those preset palettes.

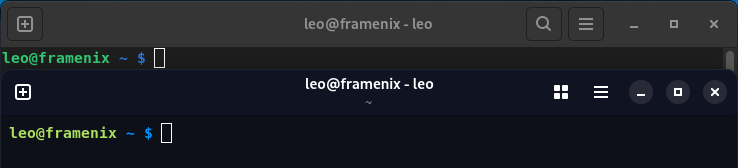

User Experience

Aesthetics is not everything that matters in software (otherwise, Windows 11 should have received no complaints); functionality and user experience are as important as aesthetics, if not more important. I find Ptyxis’ user experience quite pleasant: in this aspect, I think Ptyxis is more satisfactory than GNOME Terminal.

I initially had a surprise with Ptyxis: the first thing I noticed that exists in GNOME Terminal but was missing in Ptyxis was the “Find” button. For a moment, I thought Ptyxis did not support searching the terminal scrollback. Believe it or not, in GNOME Terminal, although I was used to using keyboard shortcuts for many operations, like Shift+Ctrl+N to open a new tab, I had always been clicking the “Find” button to start a search. In fact, Ptyxis does support scrollback search (it would be crazy if a terminal emulator does not support it!); it is just that the search feature is to be activated through its keyboard shortcut (Shift+Ctrl+F). Using the search feature involves using the keyboard to type in the search term anyway, so making the keyboard shortcut the primary way to activate it (rather than a GUI button to be clicked with a mouse) makes sense.

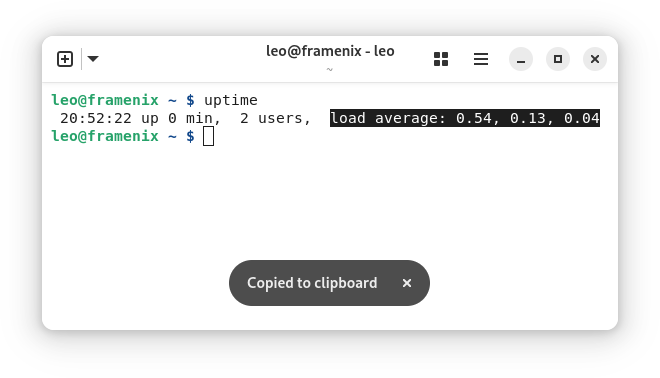

The “Copied to clipboard” toast message Ptyxis shows after the user copies some text from the terminal scrollback is a nice feature: it gives the user clear feedback for a successful operation whose outcome is not otherwise observable. GNOME Terminal does not have this feature.

There are a few additional awesome Ptyxis features for which GNOME Console deserves credit: they initially appeared in GNOME Console, and Ptyxis also implements them.

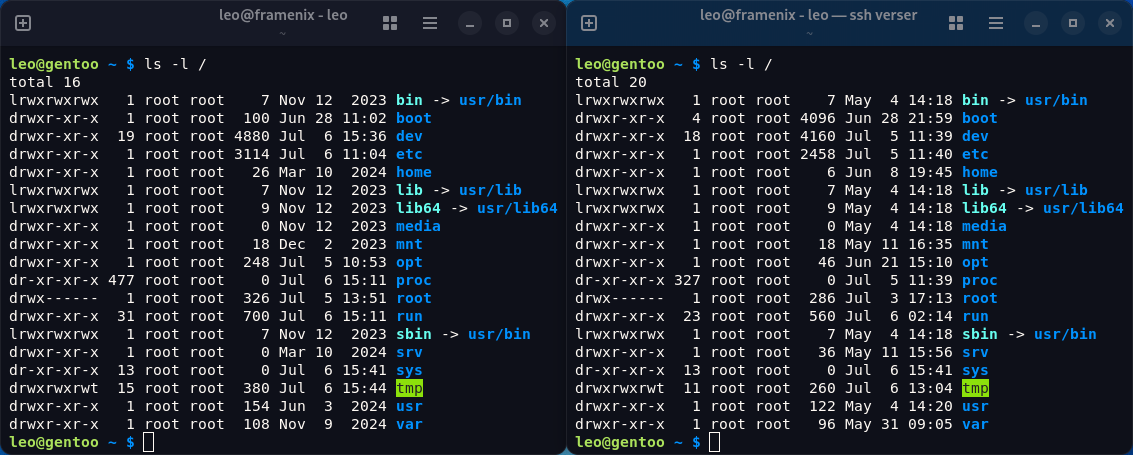

The top bar’s color changes when an interactive SSH connection is established.

I really appreciate this feature: it helps me distinguish a terminal window of

a remote machine from a local terminal window. During my time of using GNOME

Terminal, I made a few blunders of accidentally running an rm command in the

wrong terminal window when multiple terminal windows for different machines

were open. I used the wrong window because I did not set up any visual cue to

distinguish a remote machine’s terminal window from a local one.

The strategy I have been using to avoid making these blunders again is always start a tmux session after logging into a machine through SSH, so the remote machine’s terminal window is distinguished by tmux’s green bottom bar. Now, with Ptyxis, I do not have to do this anymore because Ptyxis automatically changes the top bar’s color to blue in this case.

In addition, I like the terminal size pop-up at each Ptyxis window’s bottom-right corner. As a personal preference, sometimes I would like to change my terminal window to a certain size, such as 80 columns × 24 rows. The pop-up helps me set the correct size easily.

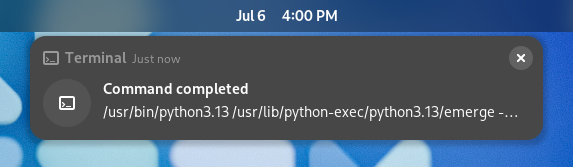

The “Command completed” notifications are also great. A few years ago, when I was using Fedora as my daily driver, I had these notifications from GNOME Terminal. However, these notifications were not GNOME Terminal’s built-in feature; instead, they were added by Fedora through a downstream patch. Therefore, on Gentoo, I have never seen such notifications when I have not applied the patch. Whereas with Ptyxis, these notifications are available out of the box without requiring any patches.